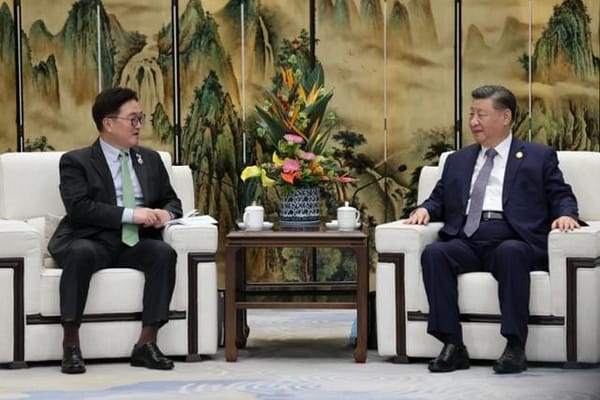

Photo: Finance Minister Chu Gyeong-ho. Credit: Ministry of Strategy and Finance.

Major indicators of the health of the South Korean economy are uniformly blinking red. For the month of June, South Korea’s two largest stock indices, KOSPI and KOSDAQ, fell by 11.9% and 16.0% respectively, suffering the greatest losses out of the world’s major stock indices. (To compare, S&P 500 of the United States fell by 5.3% in June; Nikkei 225 of Japan, 2.9%.) Finance Minister Chu Gyeong-ho 추경호 기획재정부 장관 warned that inflation may be in the 6% range through the summer, and said the cost of electricity will have to rise because of soaring fuel prices. Then there is the KRW-USD exchange rate. On June 23, the intraday exchange rate climbed over KRW 1.3k per USD 1, a rate not seen since the the 2008 global financial crisis.

The stock market dip, inflation rate and the exchange rate are all connected. The US dollar is becoming more expensive relative to the Korean won because investors are exiting South Korea’s declining asset market, changing their won-denominated assets into dollars. Weaker won makes imports - particularly petroleum - more expensive, feeding inflation. The US dollar reserve of South Korea’s central bank is declining rapidly, from USD 463b at the end of 2021 to 448b at the end of May 2022 as the Bank of Korea 한국은행 has attempted to keep the exchange rate from spiraling out of control.

To combat the won’s deterioration without exhausting its dollar reserve, South Korea could further raise the benchmark interest rate, which would reduce liquidity in the economy while slowing the outflow of capital by making South Korea’s bonds more attractive. But raising the interest rate will almost certainly destroy the real estate market, much of which is supported by variable interest loans.

For President Yoon Suk-yeol 윤석열 대통령, who was elected on the back of real estate grievances, that decision may be costly. (See previous coverage, “The Real Estate Election.”) For now, the Yoon administration is relying on heavy-handed tactics to keep the interest rate low for consumers even as the Bank of Korea is forced to raise the benchmark interest rate. Lee Bok-hyeon 이복현, a former prosecutor who was recently appointed to be the first head of the Financial Supervisory Service 금융감독원 without ever having worked for the agency, criticized the banks for “pursuing excessive profit.” The banks quickly fell in line, lowering the consumer loan interest rate by around half a point across the board.