Image: South Korea's year-to-year growth of public debt and debt-to-GDP ratio. Credit: Korea Economic Institute

Below is an op-ed contribution by the Korea Economic Institute in Washington DC. KEI hosts many events on the Korean economy and other issues related to developments on the Korean Peninsula. Sign up here to keep up to date on KEI's upcoming events.

A growing number of domestic voices are calling for the government to discipline its budget as the South Korean government expanded public spending in response to the economic fallout of the pandemic. These positions may be penny wise but pound foolish. While it is true that Korea’s debt is growing with great speed, the overall level of debt is low vis-a-vis other advanced economies. Further, concerns over the country’s fiscal soundness in the medium term overlook how public investments today are necessary to ensure a more economically vibrant future.

The Korean government has been responding aggressively to counter the economic malaise caused by the pandemic this summer. The Moon Jae-in 문재인 administration issued several economic rescue packages through a series of supplementary budgets, increasing the annual public expense to a record high of USD 431 billion and the nation’s debt-to-GDP ratio to 43.5 percent.

The publicly-funded Korea Institute of Public Finance 한국조세재정연구원 raised a red flag, calling for the growth of public debt to be moderated. Other anxious voices pointed to two potential consequences of Korea’s growing debt overhang: first, debt servicing could severely constrain future public spending, particularly as the Korean society gets older and more public spending will become necessary to assist the elderly. Second, Seoul’s inability to service its debt may lead to its credit rating being downgraded, which could trigger an outflow of foreign investments. Under pressure from these influential domestic voices, the Ministry of Economy and Finance 기획재정부 introduced a plan to maintain its public debt under 60 percent of GDP.

On some level, the anxiety is understandable. South Korea’s senior policymakers carry the residual trauma from the 1997-1998 East Asian Financial Crisis. Rising levels of under-performing loans in the late 1990s led to foreign creditors suddenly withdrawing their investments from Korea in the summer of 1997. The subsequent crisis in South Korea left deep social scars: the unemployment rate tripled and 80 percent of households experienced loss of income. From this perspective, the fact that debt-to-GDP in 2020 is growing faster than during the 1997 Crisis is understandably alarming to policymakers and the public at large.

Image: Debt-to-GDP ratio of selected countries. Credit: Korea Economic Institute.

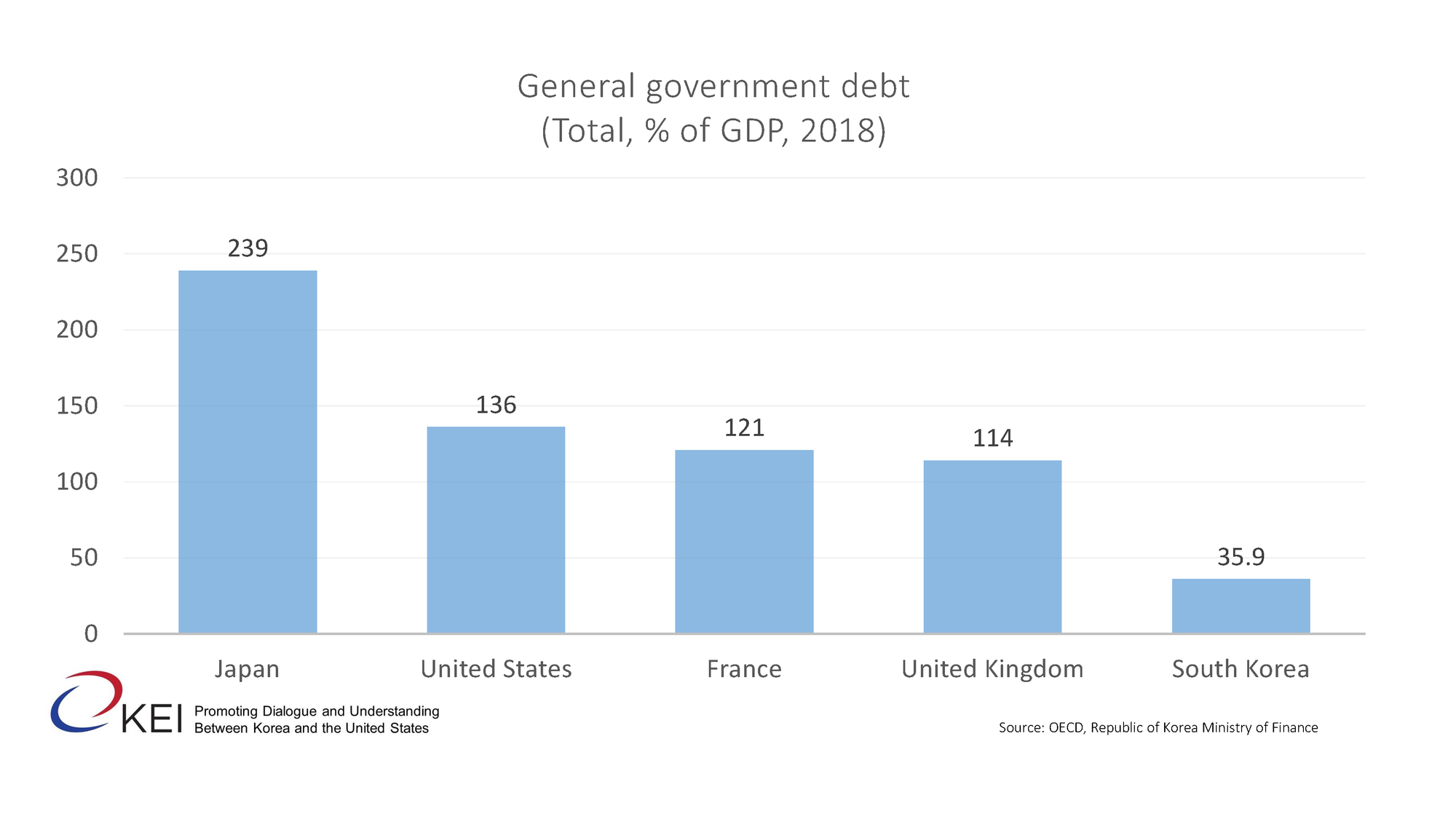

But such concerns are inapplicable today. International financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund supported South Korea’s decision to expand public spending. Credit ratings agency Moody’s also noted that even if Seoul were to hit its new debt ceiling of 60 percent, “Korea will remain less indebted than advanced economies that share a similar rating, such as France and the UK.” Korea Economic Institute 한미경제연구소’s Kyle Ferrier pointed out that South Korean public debt is still among the lowest in the OECD (for context, US debt-to-GDP ratio in 2018 stood at 136, France at 121, and Japan at 239.)

Moreover, much of the government’s spending is directed at measures to improve the country’s long-term economic productivity such as bringing more women into the workforce in preparation for the demographic aging. George Washington University International Business Professor Danny Leipziger saw greater downsides from South Korea engaging in “a tepid use of fiscal policy, such as was seen in the case of Japan, where demographics have doomed the resurgence of economic growth.” Not spending resources today might mean that Korea is even less capable of addressing the economic challenges that will remain long after the pandemic.