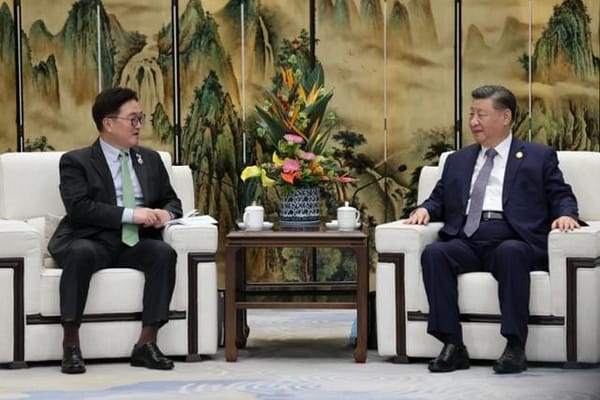

Photo: First Lady Kim Jeong-suk (right) attends the Kimchi Day exhibit. Credit: Website of the Office of the President.

The latest rendition of online flamewar between China and South Korea is a kimchi slap: the dispute, ostensibly, is that China obtained the International Organization for Standardization’s (ISO) standard for kimchi, prompting outcries from Koreans that the Chinese were stealing their culture. As these things go, the actual story is a kernel of unremarkable truth popped in the heat of sensationalistic media and keyboard warriors. The actual ISO standard obtained was for pao cai, a Sichuanese pickled vegetables dish that is clearly distinctive from kimchi. (The standard, in fact, says: “This document does not apply to kimchi”; however, some confusion may have arisen from the fact that in Chinese, kimchi is often referred to as pao cai.) The Korean media picked up provocative blog posts from China that overstated the significance of the ISO standard; the Chinese media, in turn, noted the Korean media was very mad online.

This echo chamber of competing nationalism has been a recurring feature between China (and Taiwan) and South Korea for the past decade-plus, with a rotating cast of different cultural tropes. In the mid-2000s, Taiwanese media was abuzz with charges that Koreans were claiming Buddha was Korean, citing a non-existent article on Chosun Ilbo 조선일보. A 2006 article on China’s People’s Daily raged that Koreans were daring to claim Confucius was Korean - a claim that exists only in South Korea’s deranged fringe. (Responding to the charge, South Korea’s history buffs wryly noted that China under Mao Zedong was all too happy to destroy Confucian shrines during the Cultural Revolution.)

As with the case of kimchi, the outrage goes the other direction as well. In 2002, South Koreans denounced China’s Northeast Project 동북공정, a government-sponsored study of the history of Manchuria (a traditional name for the region of present day northeastern China adjacent to the Korean peninsula) that, in Koreans’ view, attempted to appropriate ancient Korean kingdoms as a part of Chinese history. More recently, in November 2020, the Chinese video game Shining Nikki - a mobile game in which the user dresses up a virtual character with different fashionable garbs - offered hanbok 한복, a Korean traditional wear, as a special item to celebrate the launch of the game’s Korean version. China’s online mob criticized the offering, claiming that hanbok was in fact Chinese, as it was a Ming Dynasty derivative. (In fact, the early Ming Dynasty clothing was derivative of Korea’s, as many Korean women were kidnapped into China during the Mongol invasions of the 13th century, and the Ming Dynasty immediately followed the Yuan Dynasty established by the Mongols.) After facing criticisms from both Korean and Chinese users, the company behind the videogame pulled not just the hanbok special item, but its Korean version altogether.

One may be tempted to dismiss these episodes as childish spats, but doing so would be a mistake. These episodes are better understood as low-intensity battles between China and South Korea to defend their respective ontological security. Under the ontological security theory, states do not merely seek physical, economic, or otherwise tangible security; they also seek the security of the state’s self-identity. It is not a coincidence that these spats began in the early 2000s, when South Korea began emerging as a major exporter of pop culture products such as television drama and pop music. South Korea’s rise as a cultural powerhouse threatens the ontological security of China (and to a lesser degree Taiwan,) which understands the history of East Asia as the Sino-centric world, implied by the self-designation of the “Middle Kingdom.” Koreans, on the other hand, base their national self-identity on their country’s fierce fights for independence and self-governance, such that the perceived Chinese appropriation of the Korean culture is felt as intolerable.

Online flame wars may be silly, but the ontological security theory cautions us to take them seriously - because in order to protect their ontological security, states are often willing to risk their tangible security. In this sense, the periodic flare-ups of charges of culture theft between China and South Korea are comparable to an arms race involving battleships in the early 20th century, or nuclear weapons in the late 20th century. The media and online mob of the two countries do not pounce on fake news and fringe theories just because they are being juvenile; it is a form of inadvertent escalation, created between parties who maximally distrust each other’s intent as they see each other as a threat. As long as South Korea and China continue on their respective trajectories as competing powers in East Asia, these spats will continue as well - and at some point, they may spill outside of the screens.